According to the United States’ master clock keeper, the U.S. Naval Observatory, 2019 was not the last year of the decade. Another reputable calendar resource, The Farmers Almanac, takes the same position. For these official sources, decades are completed with years ending with “0” and begin with years ending with the number “1.” For most everyone else, 2019 was it. Happy New Decade!

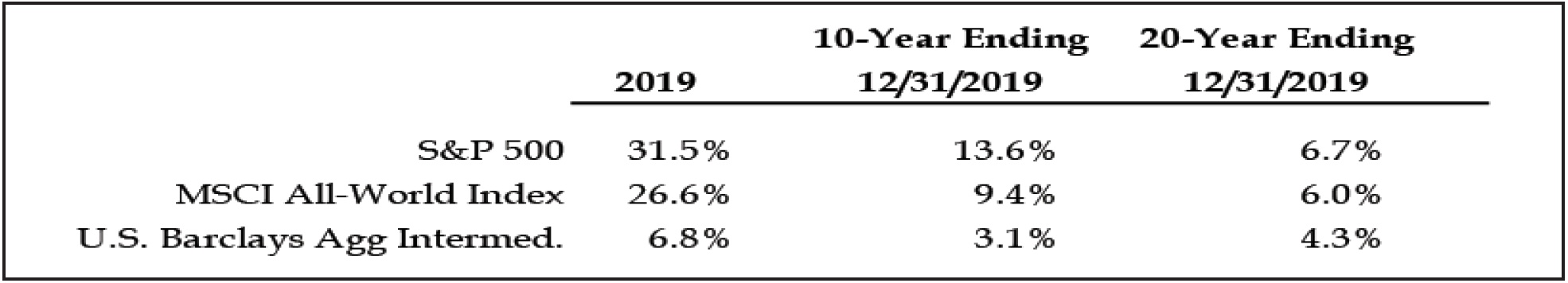

Regardless of the calendar semantics, the year was an emphatic end to a rewarding ten-year period for stock and bond investors. Up 31.5%, the S&P 500 had its best year since 2013. The index’s ten-year annualized return was 13.6%, which is well above the average price return of 8.3% since the inception of the 500 stock index in 1957 or 10.2% when the index originally began in 1926 with ninety stocks. The MSCI All-World Index, which is comprised of approximately half U.S. and half non-U.S. stocks, returned 26.6% this year. Hindered by non-U.S. stocks, which have now lagged in 8 of the last 10 years, the All-World index’s ten-year annualized return is 9.4%.

Gains were not limited to stocks. The Barclays Aggregate Bond index increased 6.8% in 2019 and has an annualized return of 3.1% for the last ten. Granted, this presumably docile asset class proved somewhat volatile this decade. An increasingly active Federal Reserve has calibrated and re-calibrated its interest rate views. Plus, aggressive quantitative easing tactics have contributed to a phenomena where now almost 30% of the world’s sovereign debt offers investors negative yields.

We’ve often discussed how the key to long-term investment success is to stay the course and expect the unexpected. The magnitude of 2019’s gains, however, surprised even the most fervent of Bulls. As for the Bears, signs of slowing economic growth, a tense trade war, and an unconventional political landscape provided an interesting setup heading into 2019. Sure, stocks in recent years had proven incredibly resilient, but these headlines were hardly the recipe for new market highs.

While the stock markets’ gains of the 2010s were historically strong, the trailing twenty-year period’s 6.7% annualized return is below average. Put another way, the 2000s were a lost decade that was somewhat recouped by the impressive Bull market of the 2010s. Yet another reminder for investors that it pays to stay the course and avoid the temptation to abandon stocks.

“Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies.” - Andy Dufresne [The Shawshank Redemption, Motion Picture, 1994]

In the following pages, we’ll discuss some of the more interesting market characteristics of the 2010s, a few trends that could give investors pause for the 2020s, and some that provide reasons for hope.

As for hope, it could have been easy to lose it this decade. Today’s media delivery model is incented to create angst and stir up controversy. And, of course, we face many serious issues, including a “crisis of loneliness,” opioid epidemic, and an increased incidence in domestic terrorism. On the fiscal front, there are mounting levels of debt and other unfunded liabilities at the local, state, and federal levels (here and abroad). This will present long-term challenges for which our politicians seem ill-prepared, or at least unwilling, to address anytime soon.

Yet, it is not all doom and gloom. A recent Wall Street Journal opinion piece entitled “The 2010s Have Been Amazing” highlighted research from the United Nations and Cato Institute detailing improvements in health and poverty conditions around the world. Specifically, from 2008 to 2018 individuals living in “extreme poverty” fell from 18.2% to 8.6% of the world’s population. That’s one billion people fewer in a ten-year span. For the first time ever, half of the world’s population is considered “middle class.” Global life expectancy has increased three years just this decade, and malaria incidents in Africa have fallen 60% since 2007.

As much as we complain about technology, the decade has brought on many life-changing innovations, most (not all) of which we wouldn’t return given the choice. These include new engines and energy sources that improve the air we breathe, devices to help our teachers teach, and tools that dramatically reduce the time from health diagnosis to treatment. For context, early this decade most of us began carrying a hand-held device with more computing power than was available in the entire world in 1969 when we first sent men to the moon.

There are no guarantees these living condition improvements can continue, let alone, persist. Countries like Venezuela, North Korea, and many parts of Africa and the Middle East have experienced tragic democratic and economic setbacks, reminding us both how special and fragile our system is. The decade’s global health, economic, and technological progress, however, provide us with hope that the 2020s will include more amazing surprises.

Not All Assets Are Created Equal, and the Winners Are Known to Fluctuate

Source: WIC, S&P, and FactSet.

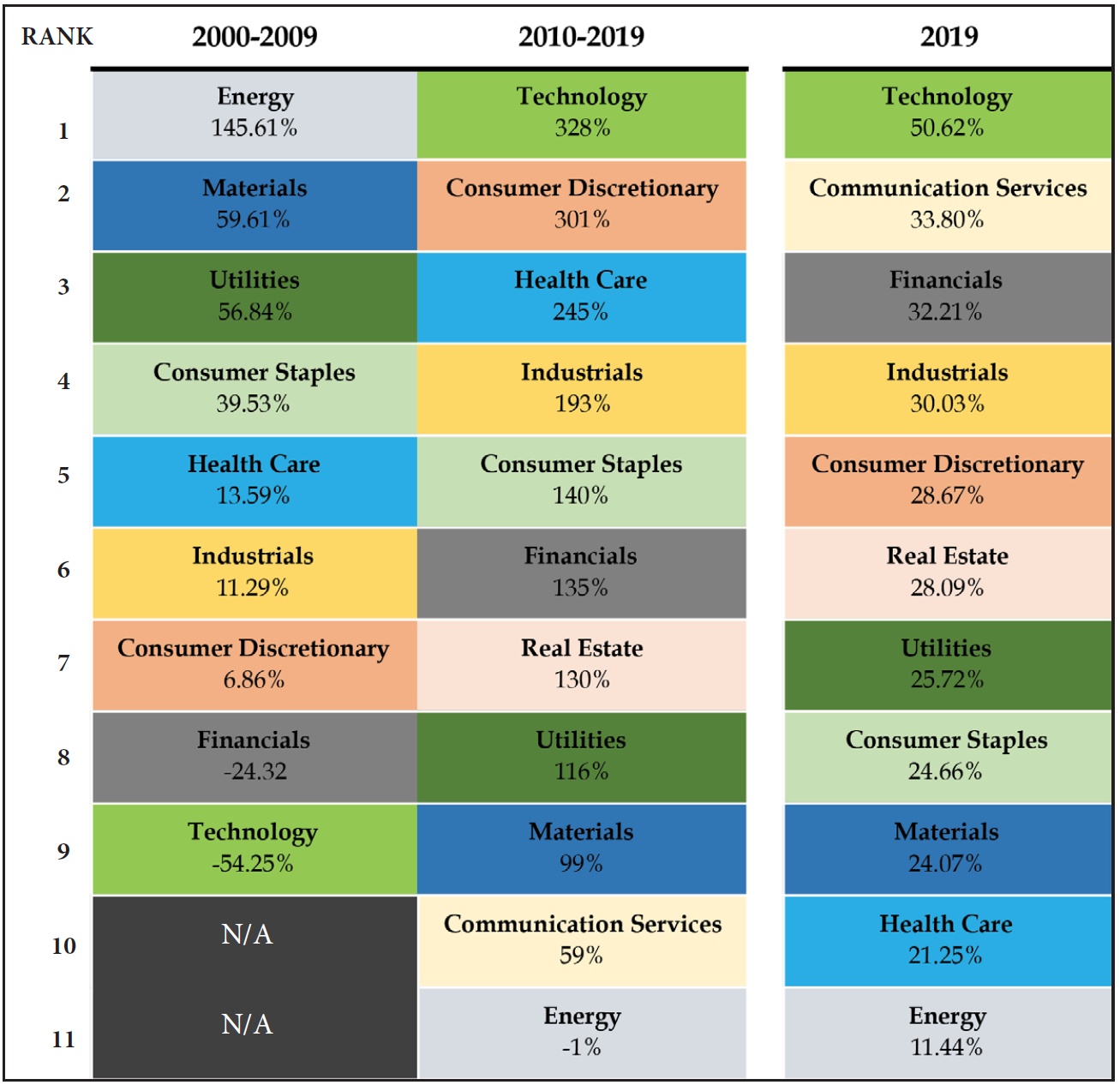

In many respects, 2019 was a continuation of the investment themes we experienced throughout the 2010s. U.S. technology and growth stocks lead the way while value, more defensive dividend payers, energy, and non-U.S. stocks lagged. The table below highlights the wide range of performance between U.S. equity sectors both in 2019 and the two most recent decades.

Not surprising, as a result of the recent sector performance gaps, the valuation divides have widened as well. The chart below highlights the extent to which many higher yielding dividend stocks (e.g., financials, energy, and consumer stables) trade at significant discounts to lower yielding growth stocks. This has created an environment with attractive opportunities for income-focused investors willing to research individual companies and invest independent of an index increasingly dominated by a handful of high-profile growth stocks.

The performance disparities among asset classes is noteworthy as well. Alternative investments, which are typically designed to be less correlated with the major market indices, gained popularity after performing well during the financial crisis. Yet, as is often the case, just as fund flows into the strategies peaked, the performance stalled. Emerging markets provide important portfolio diversification and exposure to long-term demographic growth trends, but the 3% annualized return this past decade has been a relative drag. Cash, which earned nearly 4% during much of 2000s, yielded less than 1% for most of the 2010s.

Limited exposure to the winners and too much exposure to the laggards during the last decade would have been painful. To assume a reversion to the performance mean is inevitable is too simple a solution when contemplating the opportunities for the next decade. Each decade brings new challenges, opportunities, and different sector constituents. We recognize, however, history suggests many of today’s winners could be tomorrow’s losers and construct portfolios accordingly. Put another way, we will continue to rebalance periodically and avoid chasing the winners at the expense of maintaining a well-diversified portfolio.

The Decade’s Secret Sauce

Besides the benefit from lapping the lost decade of the 2000s, factors contributing to the strong stock returns of the 2010s and which could fuel or detract from the 2020s include the following:

- Economic Growth: The economic expansion that began in 2009 is now the longest on record. The record recovery has certainly boosted investor confidence and increased the appetite for risk assets such as stocks. Yet the recovery is still below previous peaks in terms of cumulative growth, which when coupled with the potentially lingering boost of the 2017 tax cuts and other fiscal stimuli may mean the expansion still has room to run.

- Low-Rates: In early 2010, the Ten-Year U.S. Treasury stood at 3.9%. Today it is at 1.9%. The German Ten-Year yield is negative 0.2% versus a positive 2.1% to begin the decade. As much as anything, the 2010s may be known for accommodative central bank policies around the world. Tired of the paltry returns offered by bonds, many investors found solace in the stock market. Of course, it’s impossible to know with a high degree of confidence whether we return to a more normal interest rate environment, rates follow Europe and go lower, or spike if inflation reemerges. This extreme range of outcomes is partly why when comparing today’s stock and bond valuations, one would be hard pressed to conclude bonds are priced attractively, particularly those bonds with some credit risk. Therefore, we believe the opportunity within fixed-income remains limited to its role in a capital preservation and modest income strategy.

- EPS Growth & Multiple Expansion/Contraction: As we’ve discussed before, what investors are willing to pay for future corporate earnings (i.e., the Price to Earnings ratio) can have more impact on stock price changes than the earnings themselves. Surprisingly, given the decade’s big gains, the 2010s saw little in the way of P/E multiple expansion among U.S. stocks with the S&P currently trading at 18X 2020 estimated earnings. In fact, an analysis first made popular by Jack Bogle and recently revisited in Fortune reveals only about 1% of the 1X% annualized return of the 2010s was the result of a higher P/E ratio. Instead, earnings growth (+10.5%) and dividends (+2.0%) fueled most of the gains. By contrast, the lost decade of the 2000s suffered from the double whammy of a contraction of the market P/E multiple and less than 1% annual earnings growth. Ten years from now when looking back the decade’s stock performance it will likely have hinged on whether multiples expanded or contracted from current levels. While certainly not cheap, we are entering the new decade well below the record valuations of the 1990s that preceded the lost decade of the 2000s.

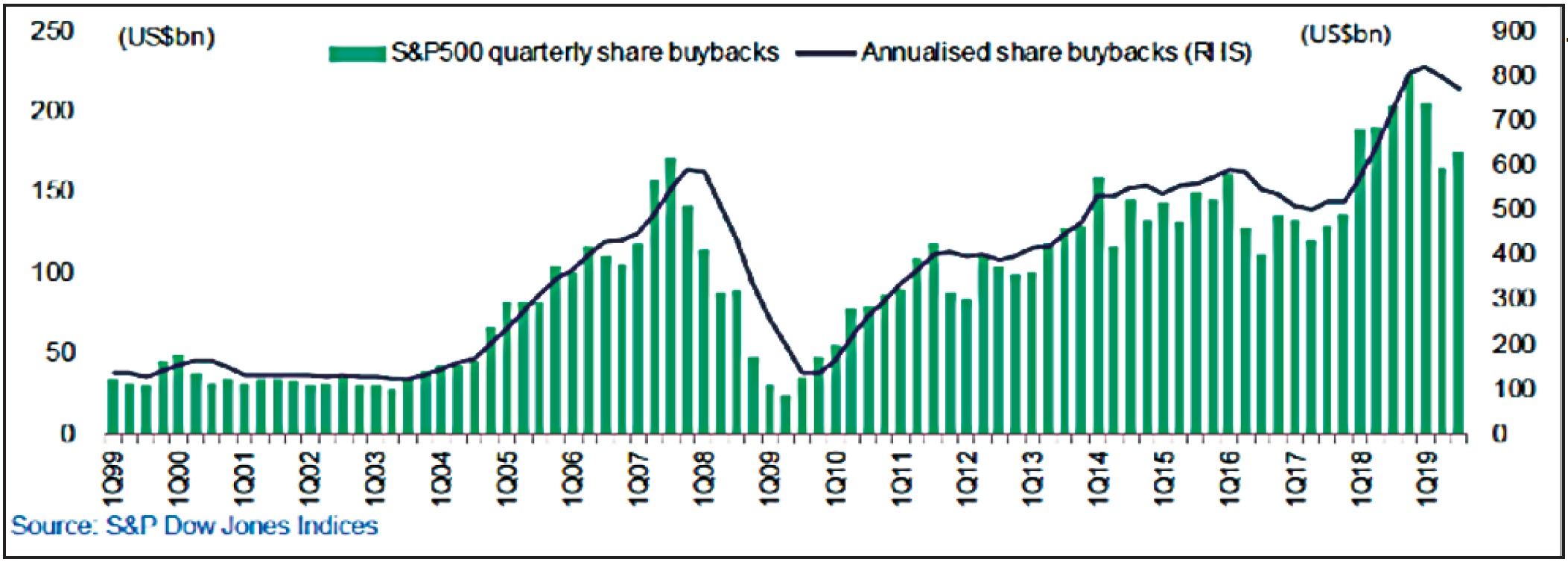

- Stock Buybacks: Aggressive stock repurchases are a potentially underappreciated component of the decade’s stock gains. According to Ned Davis Research, S&P 500 constituents repurchased $3.5 trillion in stock between 2011 and 2018. Some expect repurchase activity to approach $1 trillion in 2019. A Jefferies’ analysis reveals that, in general, the repurchase cash has not exceeded cash generated from operations and, despite the growth in activity, corporate research and development investments have been maintained. Thus, concerns about buybacks at the expense of future earnings may be overstated. Nevertheless, even in the context of a $30 trillion S&P market capitalization, the growth in buyback activity has provided a significant bid for stocks (particularly among many of the large-capitalization market leaders). Whether this buyback activity was the secret sauce of the 2010s and these levels can be sustained in the 2020s remains to be seen.

Decision Makers Are Concered About Global Trade

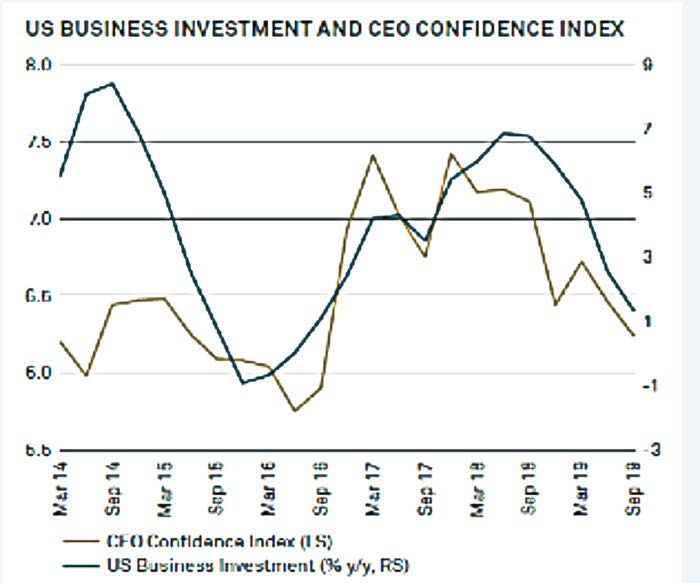

Politicians around the world have adopted a notable anti-trade tone in recent years. While there are wide-ranging views on the merits of our historic trade policies, most business leaders tasked with deciding whether to invest private capital believe free and fair trade are key ingredients to long-term economic growth. In fact, BNY Mellon recently argued that while the economic toll of the current U.S.-China “tit-for-tat tariffs” is minimal, how the uncertainty is weighing on business leaders’ sentiment is troublesome for economic growth. In other words, a “fear of de-globailization” versus any actual de-globalization could be what leads us into recession.

Source: BNY Mellon

Investors recognize the connection between sentiment, investment, and economic growth. Thus, a resolution to the U.S.-China trade negotiations, and the trade rhetoric from the 2020 Presidential election, are likely to have significant ramifications for the markets. Investors recognize the connection between sentiment, investment, and economic growth. Thus, a resolution to the U.S.-China trade negotiations, and the trade rhetoric from the 2020 Presidential election, are likely to have significant ramifications for the markets.Considering today’s historically low interest rates leave central bank policy makers with limited ability to stimulate growth by lowering interest rates, the market reaction to any new trade angst could be exacerbated.

A New Decade = New Rules for Retirement Accounts

Tucked away in a year-end government spending bill were the contents of the “SECURE Act.” While a topic of discussion for much of 2019 in the financial community, the significant changes to retirement savings plans received little popular press coverage prior to its passage in late December. Given the SECURE Act’s strongest advocates (i.e., those lobbying for its passage) were insurance companies seeking to offer often controversial annuities within company 401K plans, the stealth approach to making this sausage may come as little surprise.

The legislation includes a couple of provisions that are particularly relevant to our clients.

RMD Age Change: The age for beginning to take a Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) increases from 70.5 to 72. This will allow savers, who do not need access to their pre-tax savings, to delay withdrawals and the associated taxes for another eighteen months. Importantly, the law allows for those with earned income to make contributions past 70.5 and charitable gifts from their IRA can still be made at 70.5.

Elimination of the IRA Stretch Strategy: Beginning in 2020, non-spouse beneficiaries (e.g., children or grandchildren) of Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) are no longer allowed to stretch withdrawals out over their lifetime. Instead, any non-spouse beneficiary must now withdraw all funds (and pay the associated taxes) within ten years of inheritance. While these withdrawals can be taken over time or in a lump sum at the end of ten years, it dramatically changes the “IRA Stretch Strategy” common in many estate plans. There are some exceptions to this rule (e.g., disabled or chronically ill heirs and children who are minors), but in general it represents a significant shift in how IRA assets are treated.

Please let us know if you have questions regarding the legislation, or we can help you consider different estate strategies in light of the change to the “Stretch IRA” strategy.

Age Twenty in 2020

With the New Year comes a significant milestone for Woodmont. We will turn twenty, having first opened our doors in the fall of 2000. We’ll have more to say on this topic in future communications, including some details on how we are preparing for the next twenty and hope to serve you better. We did not, however, want to wait to express our gratitude to our clients, the CPAs, lawyers, and centers of influence who have trusted us these many years. Thank you for your continued confidence and best wishes for a rewarding new year and, at least for most of us, the new decade.